In this, the second of my blogs following my attempt to watch every film ever nominated for an Academy Award in one of the major categories, I'm going to look ahead to the ten films I'm most looking forward to watching, and the ten I'm least looking forward to watching.

Making the shortlist for these two lists, it struck me how there are way more films I'm really not looking forward to seeing, than films I really am looking forward to seeing. That strikes me as worrying at first thought, but upon thinking about it further, it stands to reason. You see, I've already seen a lot of the films that really appeal to me. Believe it or not, I tend to gravitate towards films that I think I'll like and, of the 300-odd films on my 'seen' list, I'd say probably 75% of them are films that I like a fair bit. I actually have a really good sense of what I'm going to enjoy, and what I won't, and try to avoid the latter category like the plague. This project is going to change that, unfortunately.

On with the lists, and I'll start with those films that I'm most looking forward to seeing. Auteurs abound!

10. The Grapes of Wrath (Dir: John Ford, 1940)

This is something that I've actually wanted to see for a long time, due in large part to the classic status it is afforded. It won two Oscars at the 1941 ceremony, including one for Ford's direction. I'm not typically huge on Ford (which is probably due to his close association with the Western, my least favourite genre), but he certainly knows how to make use of the American landscape, so that's something I'll be looking out for. I do like a bit of Henry Fonda, and believe this would be the earliest film of his I'll have seen.

9. Judgment at Nuremberg (Dir: Stanley Kramer, 1961)

This was nominated in a slew of categories in '62, and picked up a couple of awards. The cast is incredible- Spencer Tracy, Judy Garland, Marlene Dietrich, Montgomery Clift, and a man who has become a favourite of mine in recent months, Burt Lancaster. It looks a bit weighty (focusing on the trial of a quartet of Nazi war criminals) and comes in at over 3 hours, but with a cast like that, how could I not be excited?

8. Viva Zapata! (Dir: Elia Kazan, 1952)

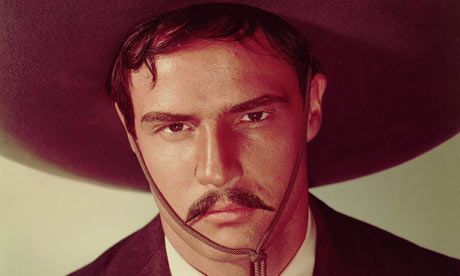

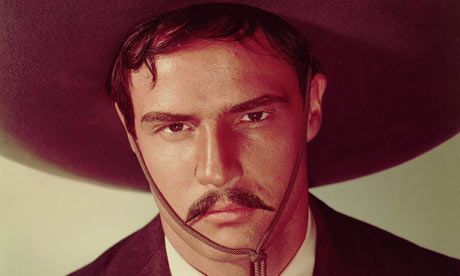

|

| Marlon Brando in Viva Zapata! |

This is the film that Kazan and Brando made together between

A Streetcar Named Desire and

On The Waterfront, and it garnered Brando another best actor nom. I know little else about it, except that Brando plays a Mexican revolutionary, but the combo of director and star makes this one I'm really looking forward to.

7. An American In Paris (Dir: Vincente Minelli, 1951)

I read an article about this film just the other day, which talked about its place within the canon of American musicals. Gene Kelly, the film's star, is someone who I consider myself a fan of (

Singin' In The Rain is one of my all-time favourite films- and didn't get so much as a nomination for Best Picture!), and he had to lobby to get this film made, as the musical was considered a dead genre at this point. The film ended up being named Best Picture at the '52 Oscars. It's been a while since I've seen a good musical, come to think of it, so hopefully this will live up to the billing.

6. McCabe and Mrs Miller (Dir: Robert Altman, 1971)

Altman is one of my very favourite directors, but this is one that has always eluded me for whatever reason. That is pretty much all the motivation required for putting this on the list, but the premise sounds great to boot: Warren Beatty and Julie Christie as a gambler and prostitute (respectively) join forces to open a brothel in the Old West. Must be a winner.

5. A Woman Under The Influence (Dir: John Cassavetes, 1974)

While my familiarity with Altman prompted me to put

McCabe and Mrs Miller on this list, it is a lack of familiarity with the director that inspires this choice. I've seen, I believe, two of Cassavetes' films (

Husbands and

A Child Is Waiting) and am eager to see more from a man who is seen as an important director in American cinema. On top of that, the star, and Cassavetes' wife, Gena Rowlands, is someone else whose work I am anxious to see more of.

4. Tucker: The Man and His Dream (Dir: Francis Ford Coppola, 1988)

|

| The incomparable Jeff Bridges. |

This may seem like a bit of an odd choice- something of a forgotten (maybe deliberately) film from Coppola's difficult later career. I actually like what I've seen of Coppola's 80s work, and respect the way he changed as a filmmaker after making some of the most critically acclaimed films of the 70s. This is all about Jeff Bridges for me though, one of my favourite actors, and someone who I'm always happy to watch. I've heard from various places that this is one of his best performances, so hopefully it delivers.

3. Cries and Whispers and

2. Fanny and Alexander (Dir: Ingmar Bergman, 1972 and 1982 respectively)

There is one filmmaker in the world I prefer to Ingmar Bergman, and his name is Woody Allen. Ever since the first Bergman I saw (

The Seventh Seal) I fell in love with his arresting visuals, and his artistic approach to tackling complex themes. He is very much a filmmaker who speaks to me on a personal level, and I have made an effort to see as much of his work as I can. Here are two that have hencetofore passed me by, and I'm really looking forward to rectifying that for this project.

1. Breaking the Waves (Dir: Lars von Trier, 1996)

I LOVE Lars von Trier. I love that he takes chances with his films, and that he isn't afraid to be hated. Whatever you say about his films, at the very least they are interesting and inspire thought and discussion. This is kind of my white whale in terms of film, as it's one that I've been trying to see for seemingly ages, but it has just never worked out. I know it was on television once, but I forgot to record; another time I saw the DVD in HMV, but for whatever reason passed up on buying it. When I returned, it had gone. Right now it's in my 'saved' queue on Netflix, which means that they don't currently have a copy. I may just have to pick up a copy online, because it's not one I'm going to miss out on!

Okay, so now moving on to the top 10 films I'm LEAST looking forward to having to watch.

10. An Officer and a Gentleman (Dir: Taylor Hackford, 1982)

A lot of the films that made the shortlist for this category are what I call 'mums films'. In other words, they are the kinds of thing that your mum owned on video, and was always watching when you were a kid. Romantic, weepie, and generally not all that good. Now, I'd actually consider myself a bit of a romantic, and certainly have nothing against a romantic film per se. It's just a lot of the time these kinds of films tend to be rather cynical in the way that they are made to tap into the, trying to put it diplomatically, female tendency towards emotional reactions. My mum did have this one, but I've managed to avoid it. Until now.

9. Inglourious Basterds (Dir: Quentin Tarantino, 2009)

|

| Tarantino: I'm not a fan. |

You'll soon learn that I have no time for the films of Quentin Tarantino (having seen all of them up until this one). I'm not sure when my dislike of his work really started. Probably around the time of

Kill Bill, although I thought he was overrated before then. Basically, I think he's the most overrated filmmaker of his time, a one-trick pony whose films are far too concerned with being 'cool' and quotable, at the expense of characterisation and emotional investment. There'll be more opportunity to talk about Tarantino in upcoming ATLI... blogs, so I'll leave it there for now. Suffice to say, despite featuring really good performers like Michael Fassbender and Daniel Bruhle, this is not one I'm looking forward to seeing.

8. Blazing Saddles (Dir: Mel Brooks, 1974)

I often get accused of being too much in favour of serious, or even grim, films at the expense of fun films. I strongly disagree with that assessment. I'm just not such a fan of stupid films. Now, I don't know that this is a stupid film, but when the most famous scene from the film consists of a bunch of guys sitting around farting, I don't see much potential there for high-brow comedy. Which is fine, but just not my cup of tea. I've actually only seen one Mel Brooks film before (

The Producers, which I wasn't a fan of), so maybe I'm misjudging him, and I'll end up a big fan. I honestly hope that is the case.

7. Shirley Valentine (Dir: Lewis Gilbert, 1989)

Another mums film. Actually, this might be the mother of all mums films- the MOAMF. This is one I do remember catching bits and bobs of when I was a kid, including a scene featuring Pauline Collins' saggy tits. This probably isn't all that bad actually, ut it just depresses me a bit that as a 30-year-old man I'm gonna have to settle down one night and watch it.

6. Chariots of Fire (Dir: Hugh Hudson, 1981)

This won the best picture award at the 1982 Oscars, and his since been called one of the most overrated films of all-time. It's probably a solid film (the cast is strong), but, like

Gandhi (the following year's best picture) it strikes me as rather dull. I ended up enjoying

Gandhi more than I thought I would actually, so there is hope for this.

5. Love Story (Dir: Arthur Hiller, 1970)

This has the reputation as the ultimate weepie, and a shining example of manipulative filmmaking. Everything about it seems totally cloying and overly-sentimental, and I'm struggling to think of anything redeeming that could come out of this.

4. The Ten Commandments (Dir: Cecil B. DeMille, 1956)

This is a three hour forty minute Biblical epic! I don't think any film should ever be that long, and I'm not a fan of these swords and sandals-style epics to begin with. I generally don't like to watch a film in two parts, as I feel it takes me out of the experience, but I just can't see doing this one in one sitting.

3. The English Patient (Dir: Anthony Minghella, 1996)

|

| Elaine Benes: doesn't rate The English Patient. |

When I think of the term 'Oscar-bait', this is usually the film that comes to mind. That said, I admit that a lot of my apprehension about this comes from that episode of

Seinfeld, where everyone at Elaine's work is going gaga over this film except her. This leads to her being fired when she finally confesses (angrily) her disdain for the film. I can only be thankful that I won't be fired if I don't like this.

2. The Blind Side (Dir: John Lee Hancock, 2009)

I was taking a shower early into my planning for this project when I realised that if I went ahead with it, I was going to have to watch this film. I could have cried. There aren't many people in the world who irritate me as much as Sandra Bullock. I don't know when or why it started, but for as long as I can remember I've found her insufferable. She looks like an escaped convict for one thing- she has the hard face of someone who has done some serious time, but at the same time wears the self-satisfied smugness of an escapee. And she makes films like this.

The Blind Side, like the deplorable

Crash before it strikes me as the kind of film affluent white people make to show their understanding of race relations. I'll wait until I've seen it to fully pass judgment, but that's the impression I get, and it really makes me feel uneasy.

1. Braveheart (Dir: Mel Gibson, 1995)

I've talked about my dislike of Tarantino and Bullock already here. Well, both of those pale into comparison to my hatred of Mel Gibson, who went from being merely a dull, smug bastard, to full-on anti-Semite, misogynist shitface. This is the one film, that when I came to it when making my list of what I had to see, almost made me abandon this whole project. I detest the man, and detest the idea of watching his historically-inaccurate vanity project.

Whew. Okay, well, I don't really want to end on such a sour note, so, as a bit of 'bonus content', I thought I'd take a quick look at 5 of the more obscure films from my 'to watch' list. Here goes:

The Sin of Madelon Claudet (1931)- This sounds rather racy for the time period, with the story including an out-of-wedlock birth, a suicide, and prostitution. Apparently, lead actress, Helen Hayes, tried to buy the film off the studio so nobody would ever see a performance that she was horrified with. Unearthing films like this is one of the reasons I'm most looking forward to this project.

The Lives of a Bengal Lancer (1935)- An early Gary Cooper film, set in colonial India. Hitler's favourite film, apparently.

The Corn Is Green (1945)- Bette Davis vehicle, which sees the original diva play a teacher in a Welsh mining town. I wonder if she'll try the accent.

Twilight of Honor (1963)- This film which apparently saw Nick Adams go to great personal expense to ensure that he received a Best Supporting Actor nomination. He promised a friend that he would be the first TV actor to win an Oscar, but lost out on the night to Melvyn Douglas for

Hud.

Who Is Harry Kellerman and Why Is He Saying Those Terrible Things About Me? (1971)- The film with the longest title on my list stars Dustin Hoffman as a successful songwriter who spends his time with various women while he tries to 'find himself'. Sounds interesting.

Well, that's it for this time. ATLI... #3 will feature the first film I've ticked off my massive 'to watch' list, and I'll also be starting to back review stuff I've already seen, with a look at the 1999 Best Picture nominees. Until then, here's looking at you.

_01.jpg)